January 29, 2016

By Ken Duckworth, M.D.

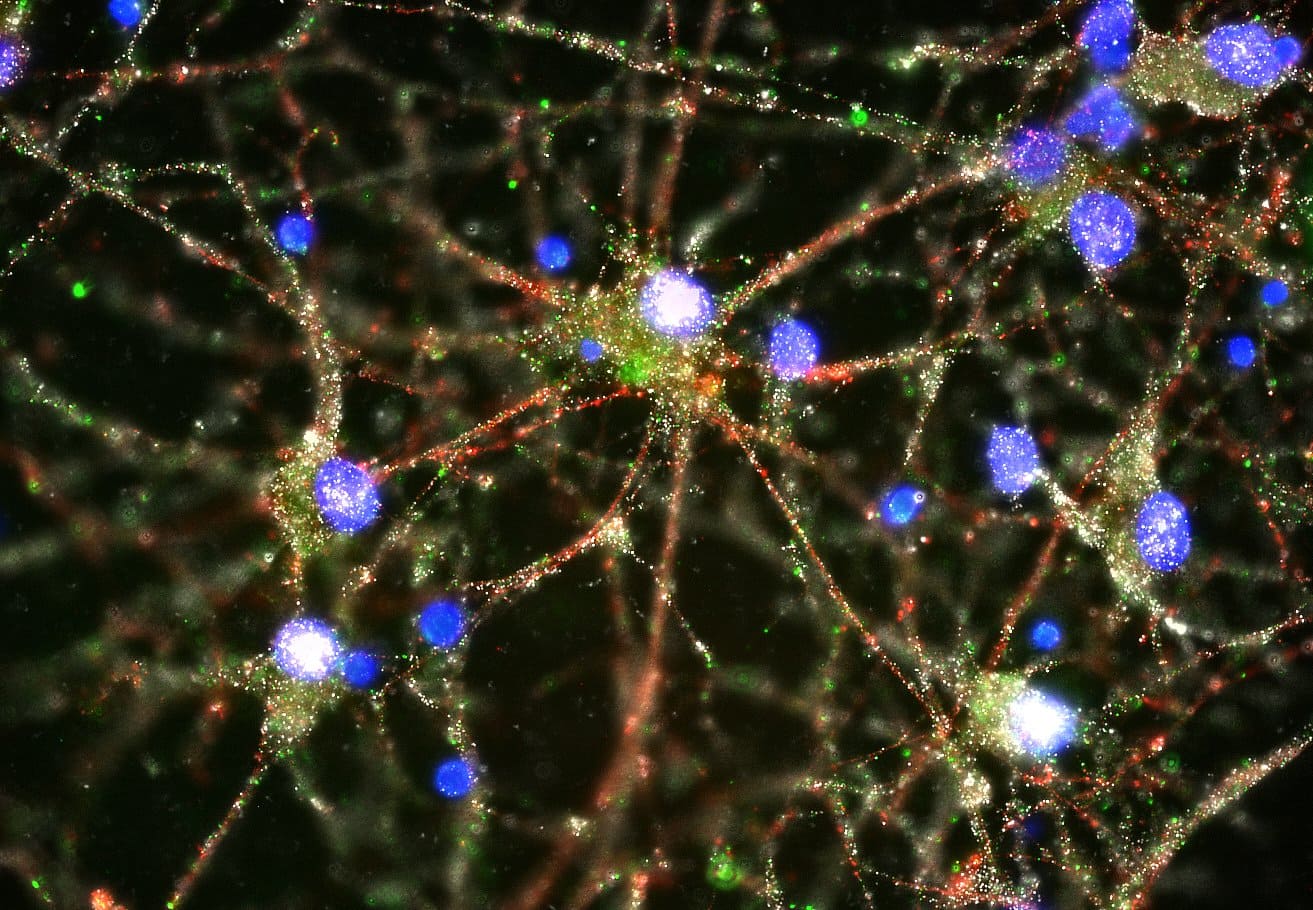

Imaging studies showed C4 (in green) located at the synapses of primary human

neurons. Image courtesy of Heather de Rivera (McCarroll lab).

In the scientific journal Nature, researchers from the Broad Institute, Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, among other sites, found a hypothesis that could be a key cause of schizophrenia. The researchers noted that people who had schizophrenia were more likely to have a certain type of a gene that promotes neural “pruning.”

Pruning is the process of the removal of neurons. In 2014, when I attended the Broad Institute’s announcement of the $650 million gift from Ted Stanley and panel discussion on a study that identified 108 genes associated with schizophrenia, I congratulated Dr. Steve McCarroll on this development. He told me that the papers on Broad’s work connecting genes and mental illness would only get more interesting as we moved forward. This new paper shows he was right.

First, let’s take a look at the hypothesis that the research supports. It has been a point of discussion for years that over or misdirected pruning may be connected with the occurrence of schizophrenia. Pruning is part of normal brain development during childhood, and especially during adolescence. After pruning takes place, new neurons are produced with more efficient functions. In other words, pruning helps the brain develop more superhighways and fewer back roads. Clinically, this hypothesis is also compelling, as the onset of symptoms often occurs in adolescence. However, we haven’t had biological facts that back this idea up—that is, until this study.

The need to understand neural networks—how neurons relate and communicate—has also gained traction in informing our thinking about schizophrenia. Pruning also fits the idea that the network of neurons could be impacted by changes in neuronal architecture. This way of thinking about the relationship of neurons in networks is one reason that we don’t use the term “chemical imbalance” anymore to explain how schizophrenia develops—that is likely far too simple a model.

At my clinic when patients, or their parents, ask me what caused their schizophrenia, I have to tell them that unfortunately we don’t know. I tell them that we think it’s a complex interaction of genes and environment that promote risk at critical stages in brain development, and that it’s pretty theoretical. This paper will most assuredly help improve my answer to this question. Over time I hope that we can understand the mechanism of the treatments we use, and why certain environmental acts like sleep deprivation or the use of stimulants and marijuana can raise the risk for psychosis in vulnerable people.

As I read it, the study does not prove that the pruning hypothesis is correct, but it does add a very compelling point to support it. Since I am a clinician, not a geneticist, my explanation of what was discovered will be rather simple, but what the researchers found is a spot on chromosome 6, called C4, which is a gene that promotes pruning. Subtypes (called alleles) of this chromosome are found in overabundance in association with schizophrenia.

The researchers in the study drew upon a number of biological ideas and pulled them together to make this observation. For example, they found that alleles of C4 have been found to promote neuronal pruning in mice after they are born, and that they are also involved in the development of neuronal networks. How gene structure connects to brain development will be an ongoing and compelling area of inquiry. This paper also represents a new level of cooperation among many types of researchers, which bodes well for our speed of future understanding.

I recall the fear and anxiety that existed when I was on the first AIDS unit in New England as a medical intern in the 1980s. We didn’t know what caused the condition, and that added to our fear, hopelessness and pessimism. It seemed overwhelming and unrealistic to contemplate a biologic solution to this devastating condition. Now, of course, we know the details of the virus and transformative treatments have followed. HIV has gone from a lethal diagnosis to one that can be lived with, and that change started with science on the underlying biological cause.

The brain and our understanding of the causes of schizophrenia will be much more challenging to master than even this complex virus. Making sense of the underlying biological properties that lead to schizophrenia will make a difference in our understanding of the development of the condition. That is the vision that the late Ted Stanley supported when he made a huge donation to the Broad Institute. As our understanding continues to grow, we will find better treatments. This study is another big step in a very long journey.

Ken Duckworth, M.D., serves as medical director for NAMI. He is double board certified in adult and child and adolescent psychiatry. He has also completed a forensic psychiatry fellowship.

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices.

LEARN MORENAMI HelpLine is available M-F, 10 a.m. – 10 p.m. ET. Call 800-950-6264,

text “NAMI” to 62640, or email. In a crisis, call or text 988 (24/7).