What Has Your State Done to Improve Mental Health Care?

Author: Bob Carolla - 10/29/2013

Over the past year, state legislatures began to respond to two major events: the terrible tragedy in Newtown, Conn. on Dec. 14, 2012, where 20 school children and six teachers were killed, and the beginning of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s implementation

|

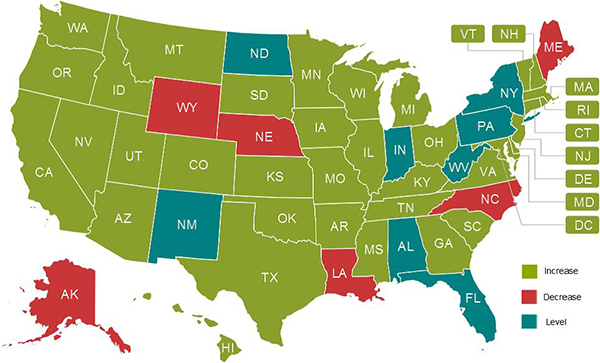

| State Mental Health Budgets Fiscal Year 2014 |

.

NAMI has prepared a State Legislation Report that is now circulating among mental health advocates nationwide. The report surveys legislation enacted by state legislatures in 2013 and summarizes trends, themes and best practices that will continue to be important in 2014.

A few issues are highlighted in this article, reflecting those that received the greatest interest from the news media throughout the year. The full report, however, is much more comprehensive and extends to the heart of many critical needs.

State Budgets and Medicaid

After years of deep cuts, states began to increase or maintain budget levels for mental health services. Mental health budgets increased in 37 states, stayed level in eight and decreased in only six. Arguably the most notable development was that Texas increased mental health spending by $259 million over two years, the largest increase in its history. South Carolina, which had cut the deepest in recent years, started to reverse that trend by increasing their fiscal year 2014 budget. While trends are encouraging, much remains to be done to restore cuts in state mental health budgets between 2008 and 2012.

Medicaid is the principal source of funding for public mental health services. Under the ACA, states needed to decide whether or not to move forward to expand Medicaid coverage. Eventually, 25 states and the District of Columbia chose to do so. However, 22 legislatures said no and debate continues in three states.

Mental Health Screening and Schools

Much public discussion in 2013 focused on the need for early identification and mental health screening for children and youth, but only five states adopted legislation to address the issue. Additionally, legislation specifically focused on school mental health training and services was passed in 10 states. Connecticut, Minnesota, Oregon and Washington set stellar examples for enacting these new policies. For example, Connecticut passed a bill that ensures teachers receive training in social and emotional development and learning of children.

In the wake of the Newtown tragedy, public debate over guns intensified. Conversations included the degree to which a person living with a mental illness should be barred from owning a gun. Debate surged regarding the circumstances under which mental health professionals should be required to identify a person with a mental illness to police authorities as potentially dangerous (duty to warn laws). Proposed legislation inevitably raised concerns about stigma, discrimination and the potential that such laws would discourage people from seeking help in the first place.

Ultimately, 17 states adopted laws that involve reporting one’s mental health history for gun purchase checks. Connecticut took the most drastic approach, prohibiting gun purchases even by individuals who voluntarily admit themselves to a psychiatric hospital anytime during the preceding six months. Duty to warn laws were passed in three states, with New York provoking the most controversy through sweeping provisions in the New York Secure Ammunition and Firearms Enforcement (SAFE) Act of 2013, which expanded the duty of clinicians to warn about potential dangerousness.

Civil Commitment, Inpatient and Outpatient Treatment

Laws were enacted in 19 states pertaining to court-ordered treatment of a person living with mental illness. They touched on a broad range of issues. Delaware addressed immunity for mental health professionals who issue involuntary holds.1 Hawaii established an assisted community treatment, in some cases in lieu of involuntary outpatient treatment. Indiana adopted a “gravely disabled” standard and New York increased the maximum length for an initial Assisted Outpatient Commitment (AOT) order.

Looking to 2014

NAMI compiled the report as a tool for mental health advocates. Besides the issues highlighted above, the report outlines legislative goals for state and local leaders to consider for 2014, depending on their circumstances. Some examples include:

- Building a bridge from Medicaid to private health insurance.

- Civil rights protection and advocacy.

- Criminal justice diversion programs.2

- Early identification and intervention.

- Integrated mental health, substance use and primary care.3

- Juvenile justice.

- Mental health parity.4

- Mental health workforce capacity.5

- Outreach and enrollment of individuals in the health care system.

- Supported housing.

- Supported employment.

NAMI hopes this report serves as a valuable resource for advocates and policy makers as they continue the work of building the mental health system of the future, wherein services, treatment and supports are made accessible to all in need. NAMI advocates for a system where children, youth and adults are provided the mental health care they need to stabilize, recover and live healthy lives.