Talking with your child about emotional topics, such as their mental health, can feel uncomfortable. This can be due to the stigma involved, lack of information or even fears of possible blame.

It may seem much easier to talk about other medical problems, such as food allergies, asthma or diabetes. There is typically more information available about those conditions, they are easy to diagnosis with medical tests and people seldom think they are anyone’s fault.

Too frequently, people blame mental health challenges on the person experiencing them by saying they aren’t trying hard enough, or they are doing something wrong. In result, we can feel like it’s our “fault,” or even our child’s “fault,” when they are facing mental health challenges.

However, openly talking to your children is a great way to help decrease this stigma. It can be tough to know how to start the conversation — let’s consider some helpful ways to talk with your children about their mental health.

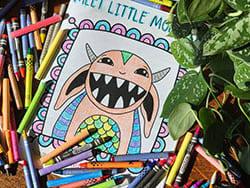

“Meet Little Monster” Coloring & Activity Book

To help foster dialogue between children and the safe adults in their lives, as well as provide children a tool for helping express and explore their feelings in a fun, creative and empowering way, NAMI offers “Meet Little Monster,” a mental health coloring and activity book, available for download at no-cost.

To help foster dialogue between children and the safe adults in their lives, as well as provide children a tool for helping express and explore their feelings in a fun, creative and empowering way, NAMI offers “Meet Little Monster,” a mental health coloring and activity book, available for download at no-cost.

Created by NAMI Washington, “Meet Little Monster” was developed in response to both the COVID-19 pandemic, when children were suddenly cut off from their friends, teachers, coaches, club leaders and school counselors, and the Black Lives Matter protests for racial justice after the murder of George Floyd. The book also includes a list of mental health resources.

Download “Meet Little Monster” Coloring & Activity Book

Make An Analogy To A Medical Problem

Children often hear about their medical problems. They understand that if they have asthma, their lungs and airways tighten up in response to dust, pets, cold or exercise. They know that the wheezing makes them uncomfortable, so they need to take medications for relief and avoid situations that may trigger an attack.

Similarly, you can let your child know that mental health concerns, like anxiety, depression, ADHD and OCD, among others, are also physical conditions that start with their brain. The brain controls feelings, thoughts and behavior — like the “central headquarters” of the body. Sometimes, the brain gets “knocked off balance,” but, like other medical problems, they can learn to manage this with treatment, which can include medications and behavioral support (stress reduction, relaxation, psychotherapies, etc.).

Give Them Concrete Explanations

Children can understand mental health issues better if they have a concrete explanation. Here is an example of how you could explain panic attacks:

“If you walked across the street and a car was about to hit you, you would jump out of the way, feel scared, have a racing heart, feel dizzy or hyperventilate (breathe too fast). All of this is a normal fight-or-flight response to a real threat of danger. A panic attack can include all the same physical and emotional reactions, except there is no car about to hit you. And while this might seem scary, there are ways to deal with it.

Many times, panic attacks happen in ‘normal’ situations, such as going to school, riding in a car, going up in elevators, and in other settings that are not actually dangerous. If you had panic disorder, you would most likely associate those places with panic. In other words, your brain would react as if something bad is going to happen, maybe even just from thinking about those situations.”

Listen To Them And Validate Their Experiences

Because there is often stigma attached to mental health conditions, children can feel ashamed to talk about their worries, obsessions, compulsions, impulsivity and other behavioral problems. Talk with them about what they are experiencing. Listen with curiosity and empathize with them.

It may be helpful to tell your child about other people who experience similar problems. If you or someone else your child trusts have mental health conditions, explain that the same way you would tell them about diabetes. These things can run in families, and they are not the only people who feel this way. If you or a family member can have a conversation with your child about their own mental health and how they manage it, it can be very reassuring.

Be Sure They Know This Is Not Their Fault

Many children with mental health conditions can feel that their condition is their fault or that it is an unchangeable feature of their personality or their identity. Stigma and misinformation often reinforce these feelings. You can help them see that mental health conditions are common and that it is not a sign that something is wrong with them as a person. Emphasize their strengths so they don’t see their mental health condition as the most important part of who they are.

Have Frequent Conversations

Many mental health conditions are considered intermittent — the symptoms can come and go throughout life and may fluctuate in severity depending on age, level of stress or any number of factors. It helps to have conversations about emotions, thoughts and behaviors that are a part of your child’s condition from the time it begins.

As they grow up, become more mature and are better able to understand themselves and their condition, your child will see you as a trusted resource they can consult if they have a relapse or experience new symptoms. Although it may not always be easy, maintaining an open and understanding relationship can be critical. Touching base with your child about their experiences is the best way to identify any new or developing issues and ensure they have the right treatment and support.

Let Them Ask You Questions

Children will have all sorts of questions about their symptoms and treatment, so being open and giving them information about the ways therapy and/or medications can help will be reassuring. If you do not have all the best information, plan to meet with your child and their mental health clinician together to discuss the problem and their questions. If your child asks a question you don’t know the answer to, it’s ok to say you don’t know and then work together to find an answer.

Include The Family

Ideally, a mental health condition should not be a secret. Your child may feel more secure if their siblings/ grandparents/others in the family know about it, can talk with them about it and accept it — just as they would accept any other medical problem, like diabetes. This kind of transparency is incredibly helpful to prevent feelings of shame or isolation.

Discuss Self-Care And Prevention

Mental health conditions are a complex interaction between biology, psychology and environmental factors. Teaching your child to practice self-care, including maintaining a healthy diet, exercising regularly, meditating and getting sufficient sleep, are instrumental in preventing relapses and diminishing symptoms.

Don’t Be Afraid To Ask About Suicide

In recent years, rates of death by suicide and suicidal thinking have increased in young people. Many parents and caregivers are wary of asking a child if they have suicidal thoughts, intentions or plans. They may be afraid that starting the conversation may cause suicidal behavior, but this connection has proven to be false. Asking about suicide may be a relief for people of all ages. If your child has a mental health condition, it’s important to check-in with them about suicidal thoughts.

Talking with your child about their mental health condition is not easy. However, you are more than capable of opening a dialogue.